Introduction

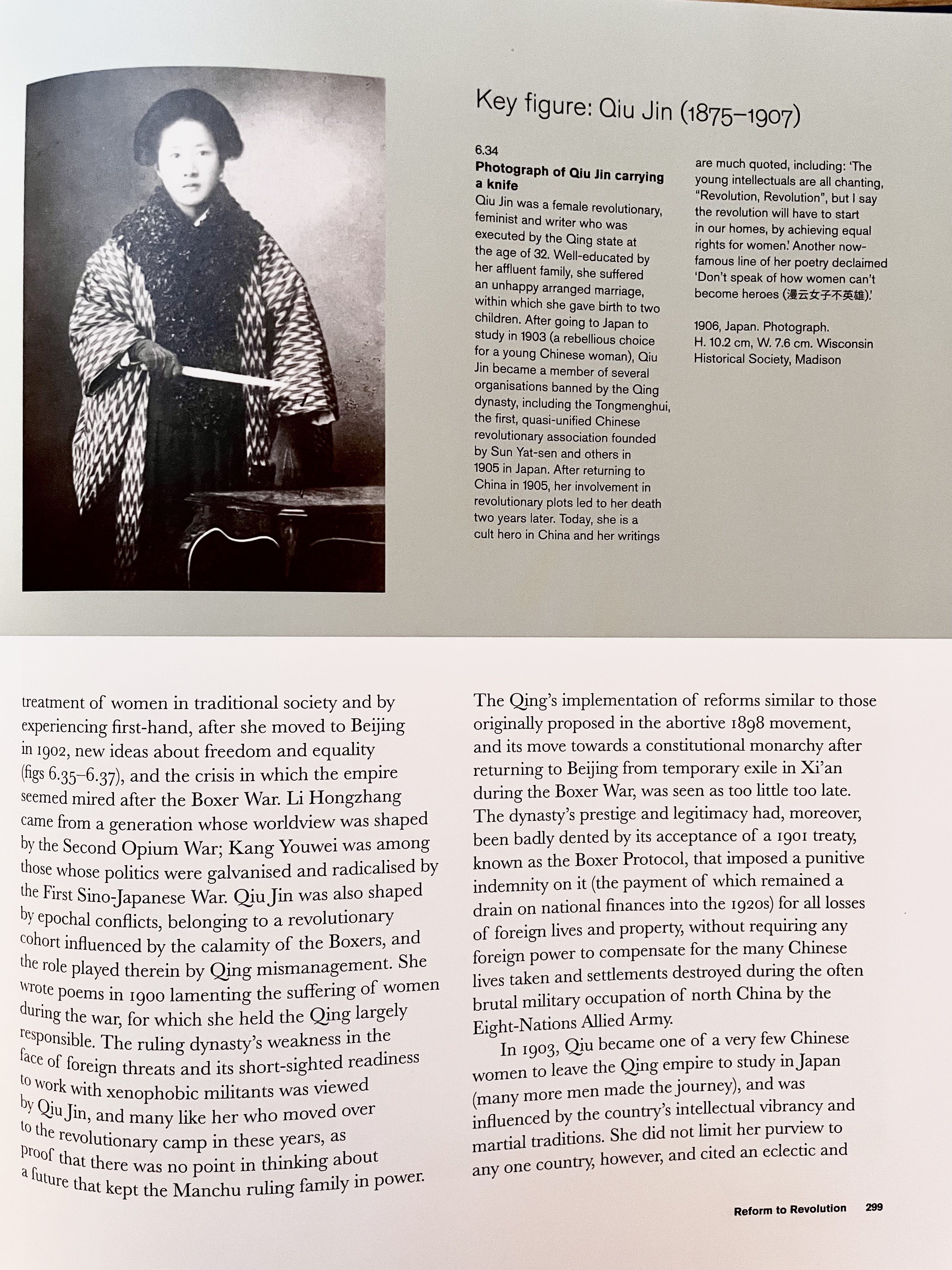

This page aims to present a detailed timeline of the events surrounding the British Museum’s use of my translations of poetry by Chinese feminist poet Qiu Jin without credit, permission, or pay for over a month in their “China’s Hidden Century” exhibit in 2023.

A settlement was reached only after I fundraised to obtain legal representation and prepared to sue. In the end, my translations were restored to the exhibition with full credit, modest compensation, and the museum admitted to not having a clearance policy for translations. The case sets an important precedent for translators.

But there remains a lack of accountability and little explanation for exactly how my translations ended up in the exhibit without permission and who actually put them there. I created this page to combat misrepresentation and gaslighting. I have included everything that I feel comfortable sharing publicly, including extensive receipts. I encourage folks to link to this page whenever you discuss the incident.

May 22nd-early June, 2023: Initial encounters with the exhibit

- I saw on Facebook that a British Chinese writer I know, Lijia Zhang, had posted about contributing to the Qiu Jin section of the exhibit.

- When I asked her what the Qiu Jin section included, given my interest in her work as a translator, I learned the section focused on her poetry.

- I was surprised by this information given that I am one of very few translators who have translated Qiu Jin’s poetry, and as far as I know, the only poet to do so, but since Lijia was familiar with my translation work from our past conversations and didn’t say anything further, I figured there were no translations or other people’s translations were used, and didn’t think more about it.

- Other folks I know also brought the exhibition to my attention, letting me know that Qiu Jin was featured, and one person even asked me if my translations were used.

Lijia’s Facebook post was one of the first places I heard about the exhibit

Conversation between me and Lijia in the comment section of the above post

June 17, 2023: Sudden discovery of my translations of “A River of Crimson” used without permission, credit, or pay

- I was taking a break from writing my essay on translating Qiu Jin’s poetry for my forthcoming book, The Lantern and the Night Moths, and chanced upon a video on Bilibili about the exhibit, which featured my translation of Qiu Jin’s “A River of Crimson.” I discovered more videos and photos on social media.

- I was shocked since I had never granted permission and was never contacted. I was not credited and obviously not paid.

- Lijia was credited as a writer on the slide immediately after my translation of “A River of Crimson,” while I was not. She is the only person credited in the whole video projection.

- Given that she had read my translations and discussed them with me before, I was truly shocked she didn’t tell me and that I was not credited while she was.

- I posted on Twitter in a thread that has since then gone viral, demanding a public explanation and accountability from the British Museum. I used #NameTheTranslator given there is a long history of translators not being cited for their work.

- I also posted to ask for more people to share information about the exhibit and the poetry from Qiu Jin being used, since I couldn’t physically visit.

- My translations of Qiu Jin’s poetry had first been published in China Channel and Asymptote.

- “A River of Crimson,” featured in the above video, was first published in China Channel on February 12, 2021.

June 17-18, 2023: Discovering the extent of use without permission and encountering gaslighting

-

- I confronted Lijia in private and gave her a chance to respond.

- She acted as if she had never encountered my translations before, despite having first connected with me in 2021 after reading those translations in China Channel. We have discussions of translations of Qiu Jin’s poetry that span a year and even had a phone call about it.

- She also tried to “congratulate” me upon hearing about work being featured without permission.

- I confronted Lijia in private and gave her a chance to respond.

- I continued to collect more evidence on Twitter as multiple people sent me photos of my translations being used in connection with the exhibit.

- I again confirmed that they used my poem “A River of Crimson” (a 23-line poem used in full with multiple incorrect line breaks introduced) in a prominent project video (the video posted above).

- The British Museum used additional excerpts on panel descriptions, in a transcript of an audio guide, and in the exhibit’s print catalogue (where there was one single footnote, a partial citation). Again, all of this was done without permission.

- There were and are still rumours being spread that the catalogue had complete and full citation from the beginning, as a defence for the British Museum’s full intentions to cite in the exhibition, but this completely overlooks the fact permission was never sought.

- It is also NOT true the book had full citations, because below is a page where credit and citation were omitted. I ask people to stop misrepresenting this immediately.

June 18: First round of emails with the British Museum where they express they are “grateful” to me for helping to “make this exhibition happen”

- Jeff Wasserstrom, the academic who wrote a chapter on Qiu Jin for the exhibit’s print catalogue, reached out to let me know that he cited my translations from Asymptote in his chapter [which I have confirmed is one single footnote at the end of the book].

- Jeff told me that he was not involved in putting on the exhibit. This further confirms that the one footnote in the book catalogue cannot be used as a defence by the British Museum for not seeking permission for the exhibition itself.

- In regards to the catalogue, Jeff told me “I think be [sic] cited there has lasting value”, implying that I should just be grateful for my work being used (despite the lack of permission).

- Jessica Harrison-Hall, an organizer of the British Museum exhibit and a staff member in the Department of Asia, finally reached out.

- She misrepresented the situation as an “innocent omission” where they just forgot to credit me on the acknowledgements panel.

- She stated “400 people in 20 countries have helped make this exhibition happen and we are grateful to you all” when I was not helping to make it happen; I was never asked.

- There is absolutely no acknowledgement of the theft of my translations, but they mentioned they would add my name to the “acknowledgements board.”

- At the advice of a fellow translator, I responded to the gaslighting email above and emphasized that the British Museum has no permission, so that they cannot use my translations unless they obtain permission and pay me properly.

June 19, 2023: Second round of emails explaining the British Museum is a “charity” and many contributors let them use work “without charge or for a small fee”

- After some emails requesting a phone call, which is very difficult given the 8-hour time difference and would leave no paper trail given the amount of gaslighting I was enduring, I received another email from a different British Museum staff member, Rosalind Winton, at 9:42AM PST.

- She stated that “we inadvertently omitted to obtain your prior permission to the use of your work.” I do not know how this could have happened “inadvertently” and was shocked by the passive language.

- They said they were “looking into what has happened” but I never got an explanation.

- The same email implied that they hoped I donate the work to them or let them use it with a low fee, because they’re a “charity.”

- “Because we are an academic organisation, and a charity, many of our contributors graciously agree not to charge us for the use of their work in our exhibitions, and most of the other contributors of images, text and digital media incorporated into this exhibition did so without charge or for a small fee, although we would always offer an acknowledgment for their contributions.”

- They offered to send me permission forms.

- Around the same time, I discovered that the research project behind the exhibit, “Cultural Creativity in Qing China 1796-1912,” was funded by an AHRC grant that totalled £719,000. In addition, the museum exhibit itself is ticketed, and the entrance fee is £16 per ticket.

- Julia Lovell, who is listed as the other co-investigator alongside Jessica Harrison Hall, who wrote the initial email, is a white sinologist and herself a literary translator from Chinese.

Project description of AHRC grant connected to “China’s Hidden Century” exhibit

- Julia Lovell, who is listed as the other co-investigator alongside Jessica Harrison Hall, who wrote the initial email, is a white sinologist and herself a literary translator from Chinese.

- Due to dismissive comments about literary translation, I posted publicly on Twitter about the amount of work that goes into my poetry translations:

- “I’m slowly working towards a book-length translation. For this work, I have close read through all 200+ of QJ’s poems about five times. I have published around a dozen or so. Speaking generally when it comes to my poetry translations, they take about a week to several months, perhaps an average of 20-50hrs per poem including selection, background research, annotating, translation, revisions, and seeking feedback.”

June 20, 2023: Third round of emails where the British Museum informs me of my translations have been removed, but they’ll compensate me for use in the catalogue

- While I was seeking advice from the Society of Authors and thinking through how to respond to the series of dismissive emails, and before I even had a chance to respond, I received a new email at 7:22AM PST, less than 24 hours later.

- The new email stated that all my translations have been removed, before I even got a chance to respond. Once again, the museum was acting without my input, and I was getting whiplash from the abrupt tone changes.

- They only offered to pay me only £150.00 (exc VAT) for permission to use the translations in the catalogue.

- There was no mention of crediting me or paying me for the use of my work in the actual exhibition.

- I replied letting them know that I was now acting with union advice and that my responses would be slower, and requested the permission forms they previously offered.

- I finally receive an “apology” from Julia Lovell, the co-investigator of the AHRC grant.

- In the letter, she stated that she was “completely sympathetic” but also claimed it was a “genuinely accidental, unmalicious piece of carelessness amid a very complex project.”

- She did not offer an explanation for how it exactly happened.

- She admitted that I should be paid and credited, but also stated that she had nothing to do with the installation and denied any responsibility:

- “I should also say that the installation of the exhibition isn’t an aspect of the project that I had anything to do with. The British Museum handled all design and permissions issues, including with regards to the Qiu Jin installation and the use of quotations in the exhibition. As the academic partner, I was actively kept out of that process and did not have any responsibility for it.”

- She stated she never profited, yet admitted to the grant allowing her to take a year’s paid leave to focus on the research:

- “I would also like to say that I have not profited a single penny from the project’s external AHRC funding, which has supported the realisation of the project itself, beyond the fact that the funding enabled me to take a year’s leave (within a 4-year project) from my usual teaching and administration duties at the University of London, in order to carry out research for designing the exhibition and the accompanying book. During that year’s leave, I received my normal university salary – there was absolutely no ‘consulting fee’ or anything similar.”

- I initially stated on social media that I appreciate her reaching out, but due to the various excuses and lack of explanation, I do NOT accept her apology.

June 21, 2023: Fourth round of emails offering more compensation, but refusing to reinstate or credit me; Public statement that is vague and lacks accountability

- In response to my request for a list of all the places that my translations were used, Rosalind finally provided me a chart laying out all the places in which my translations were being used.

- They admitted to my translations being used in all the following places without permission from 16 May – 20 June 2023.

- I found out the catalogue including my (partially cited) work without permission had a print run of 30,000 copies. The hardcover catalogue is on sale for £40.00 each on the museum’s website.

- They finally offered to compensate me £450 for retroactive usage in the exhibit (without permission or credit) from 16 May — 20 June and the original £150 for the book catalogue.

Chart from Rosalind’s email detailing everywhere that my translations were used

- The letter of agreement they sent emphasized they would NOT credit me and that my work “will not be featured” despite the fact they had already featured it for more than a month:

- “Please note that this payment is made retrospectively; we will not be reinstating the translations in the exhibition that have been removed following your complaint, and therefore you will not be acknowledged in the exhibition as your work will not be featured.”

- The British Museum issues their first press release about the incident, in which they do not use apologetic language but states that they have “apologized,” despite me not accepting those apologies.

- The statement is full of passive language and calls it an “inadvertent mistake” without any explanation.

- The statement misrepresents that they had removed my translations at my request, despite the fact they offered to credit me in the first email and then offered to obtain permissions, but then abruptly changed their mind with me first and refused to credit me.

- They would also go onto tell newspapers like The Guardian the removal was done in “good faith.”

- The statement spends more time criticizing unspecified “attacks” against staff than apologizing for the theft of my work or explaining what actually happened.

The British Museum’s first press release and statement on the incident -

The British Museum claims to The Guardian the removal was done in “an act of good faith”

-

June 22-27, 2023: Discovery of Qiu Jin’s Chinese poetry also being removed from the exhibit; Escalating to seeking legal advice; the British Museum continues to double down and refuses accountability

- I discovered from friends who went to the exhibit that not only my translations have all been removed from the exhibit, but also Qiu Jin’s original poetry in Chinese (which are in the public domain) were also all scrubbed from the exhibit, effectively erasing both of our work.

- I spoke with an IP lawyer and responded with a “without prejudice” letter based on his advice, requesting that the British Museum actually corrects the error by obtaining my permission to use my translations with reasonable payment and full credit, and that a sincere and appropriate public apology is issued.

- Rosalind replied in a “without prejudice” letter repeating the original June 21st refusal to credit me. They refused to obtain permission to reinstate, nor to issue a proper apology.

- The British Museum continued to refuse to reinstate the translations or credit me:

- “Making changes to a live exhibition is challenging, and we will not be in a position to make further changes to the exhibition to reinstate the works.”

- They blamed the lack of full citations in the catalogue on “the editorial approach” and “editorial style.” Direct quotes:

- “the editorial approach adopted in the book is to include footnote citations only after the last quote in a paragraph where quotation appears rather than after each quote”

- “the editorial style of the book is not to include footnote references in caption boxes”

- In response to my request for a proper apology, they stated that “the omission was not intentional but resulted from human error” and that they had “apologized” in private already so they will not issue any further statements.

- The British Museum continued to refuse to reinstate the translations or credit me:

- I kept demanding for an explanation about exactly how the “omission” happened and once again request credit and reinstatement, but they kept refusing to do so in multiple rounds of emails.

June 30-July 10th, 2023: CrowdJustice fundraiser for legal representation

- I launched a CrowdJustice fundraiser to officially fundraise for legal representation to raise money by July 10th to “bring a claim against the British Museum for its infringement of my copyright and moral rights in the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC), which is a specialist court and part of the Business and Property Courts of the High Court of Justice in London.”

- Thank you so much to everyone who helped spread the word, supported me, and donated.

- The fundraiser eventually raised £19,200 from 701 pledges.

- The large amount of money I had to fundraise at a short notice highlights the significant financial barrier to holding these large institutions accountable.

July 11th, 2023: Meeting with lawyers; letter from British Museum’s (now former) director suddenly wishing to settle

- I officially obtained the legal representation from lawyers Jon Sharples, Aimee Gavin, and Alex Watt at Howard Kennedy LLP, whose help I greatly appreciate. I especially want to thank Jon for reaching out to me initially to offer his assistance.

- On the morning of the 11th, literally less than an hour before I was about to meet with my lawyers to discuss the filing of the claim, which they had done extensive work on and were preparing to file, I received an email from the British Museum’s (now former) director, Hartwig Fischer, wishing to settle on essentially the same terms that I requested in my letter of June 22nd (and multiple times afterwards) before seeking legal representation.

- The letter was apologetic, but it was very disappointing and upsetting to receive it only after all the poor responses prior and the emotional toll of having to fundraise for legal representation.

July 12th, 2023: Letter of support

- European Council of Literary Translators’ Association issued a public letter of support. Thank you.

July 29, 2023: Petition to the British Museum

- Rebecca Hsieh and other friends of mine started a change.org petition to hold the British Museum accountable, which I greatly appreciate.

July 31, 2023: BTS ARMY Joins in the efforts to help with the fundraising

- Thank you so much to Anton, Claire, and Slin, the English translators of the book Beyond The Story, and members of the BTS Army for helping to spread the word about the CrowdJustice fundraiser. See tweet here: https://x.com/kook00san/status/1686030892240658432?s=20.

August 7, 2023: Announcement of the settlement

- It took until July 11th to early August to work out all the details of the settlement.

- I announced the settlement with the British Museum in a public statement here.

- My translations were finally restored to the exhibit, with proper credit, pay, and permission, and an amendment was also made to the catalogue for the uncited excerpt.

- I ended up receiving the fee (confidential amount) that I requested before obtaining legal representation, and asked for a matching amount that to donate, because I wanted to create workshops for BIPOC translators in light of the British Museum’s poor treatment of translators.

- The British Museum issued an apology as a part of the settlement and admitted to not having “a policy for the clearance of translations” and committed to making one by the end of the year.

-

The British Museum’s second press release, issued as a condition of the settlement

- Some additional context:

- During the settlement process in July and August, I continued to run into the British Museum offering no explanation about exactly how my work was obtained and used without permission, or who exactly was responsible. To this day, I never got those answers.

- I had to correct multiple biographical errors about Qiu Jin’s life in the materials that I came across and even dealt with Qiu Jin’s name being misspelled.

- I ran into repeated pushback when it comes to my request to correct the errors in line breaks that were introduced when my translations were used without permission. The museum repeatedly cited technical and production limitations before they finally agreed to correct it.

August 29, 2023: Donation to run two literary translation workshops

- I officially announced that I have donated the matching fee to the organization Modern Poetry in Translation to run two MPT Labs (translation works) taught by and for BIPOC/racialized translators, which will happen in 2024. Thank you so much to Khairani Barokka for helping to organize the workshops and for all the support.

- The first one is a Sinophone poetry translation workshop taught by Chenxin Jiang.

Dec 23, 2023: Discovery of NüVoices podcast where Lijia Zhang interviews Julia Lovell

- I chanced upon a podcast where Lijia Zhang, the only person credited in the original video projection featuring my translation of “A River of Crimson,” interviewed Julia Lovell, the co-investigator of the AHRC grant.

- In the podcast, Lijia and Julia discussed what happened to me and respond to the incident, but neither of them nor anyone at NüVoices informed me of the podcast, despite the fact I am named and also mentioned in the show notes.

- The interviewer and interviewee repeatedly minimized the issue as an “unfortunate, human error,” and misrepresented what happened as the British Museum just forgetting to cite at the exhibition and claimed the British Museum fully intended to do so.

- They completely disregard that my translations had been taken WITHOUT PERMISSION, and the fact I had to fundraise to threaten to sue the British Museum due to their refusal to credit me.

- Lijia described the incident as “drama” and said she felt “sorry” to Julia for “attacks,” as if they are the victims.

- Julia blamed the “design department” for the issue, when it’s clearly not an issue of design, but the lack of permission sought.

- NüVoices, an organization focusing on women voices working on research related to China, had interviewed me about my translations of Qiu Jin’s poetry in the past in 2021 and also re-published my translations of Qiu Jin’s work in Asymptote.

- In response to their decision to platform Lijia and Julia in this way, with no regard for the traumatic experience I went through this summer and the erasure me and Qiu Jin had already endured, I have now revoked the permission I granted NüVoices in regards to my translations and asked them to remove my work ASAP.

- As a result of the NüVoices podcast and other incidents of gaslighting, I have created this page to keep the records straight. I would appreciate folks sharing it and direct everyone to this page when discussing what happened.

Dec 28, 2023: NüVoices removes my translations without apologizing.

-

- NuVoices removed my translation after I notify them that I have revoked permission to publish, but they never bothered to even acknowledge what happened or apologize. It’s extremely disappointing.

Interviews and podcasts with Yilin about the fight with the British Museum:

- #NameTheTranslator and the British Museum: a call to action and interview with Yilin Wang

- Academic Aunties Episode 36: #NameTheTranslator

- The Ace Couple Episode 93: The British Museum Stole Translations of Qiu Jin’s Poetry ft. Yilin Wang

- BC Museum Association Podcast: Copy Rights and Copy Wrongs

Additional documentation:

- I want to thank the Aspects Committed to Anti-Racism group for creating a resource document fpr people to take actions to help.

- Thank you to @floodkiss and @rhythmelia for cross-posting on Tumblr.

Select press coverage in English:

- The China Project:

- CNN:

- CBC:

- Hyperallergic:

- Artnet News:

- A Writer Is Calling Out the British Museum for Using Her Translations of Chinese Poetry in an Exhibition Without Permission

- A Chinese-Language Translator Has Threatened to Sue the British Museum After It Removed Her Work From an Exhibition

- The British Museum Has Reached a Settlement With a Translator Whose Work Was Used in an Exhibition Without Her Permission

- ARTnews:

- British Museum Removes Writer’s Translations of Chinese Poetry After Being Accused of Copyright Infringement

- Writer and Translator Will File Legal Claim Against British Museum For Copyright Infringement

- British Museum Reaches Settlement with Poet Yilin Wang After Using Translations Without Permission

- The Art Newspaper:

- The Telegraph:

- The Conversation:

- NBC News:

- Museum + Heritage Advisor:

- The Guardian:

- Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators

Select press coverage in Simplified & Traditional Chinese:

- 大英博物館侵權還「羞辱專業」?──翻譯工作,一項未受到應有尊重的職業

- 大英博物館涉盜用秋瑾翻譯 事後只刪除文本未署名華人譯者惹訴訟

- 溫哥華華裔翻譯家與大英博物館就未經授權使用作品達成和解

- 大英博物馆展览上的秋瑾诗作译文抄袭风波|文化周报

- 侵权!大英博物馆未经许可 使用加拿大华裔翻译家作品

- 大英博物馆陷译文抄袭风波,向华裔译者致歉

Select press coverage in other languages:

- French: Le British Museum vole le travail d’une traductrice

- Polish: Fatalne zaniedbanie ze strony British Museum. Tłumaczka walczy o swoje prawa

- Spanish: El Museo Británico ataca de nuevo. #NameTheTranslator | Por Andrea Elizabeth Barrales Jandette

Thank you:

- Thank you to everyone who has supported me throughout this incident, whether by providing emotional support, spreading the word, donating, helping with fundraising, writing to the British Museum, creating and sharing the petition, and more.